The current coronavirus pandemic has been a gut-punch not only to ride-hailing tech giants Uber and Lyft, but to the “independent” workers who drive for them and rely on them for secondary (and sometimes primary) income.

Ride-hailing and ride-sharing demands are dramatically lower at the moment—down about 60% versus last year.

That hasn’t stopped California regulators from saying now is the time for ride hailing to clean up its act. The state is working on a way of mandating electric cars for so-called transportation network companies, and in a public workshop held last Friday via a conference call, the California Air Resources Board (CARB) provided an outline of how it might do that.

Lyft car with trademark pink mustache (via Wikimedia)

The carbon footprint of ride-hailing isn’t inconsequential. According to the state, transportation networks now contribute about 1% of the state’s greenhouse-gas emissions for the light-duty vehicle sector; and at least up to this year, that amount was growing rapidly.

According to California, transportation itself contributes to nearly half of greenhouse-gas emissions in the state, while 70% of that is attributed to light-duty vehicles.

Too many deadheads

According to California data released late last year, a shocking 39% of ride-hailing trips are “deadhead miles”—those with just the driver, heading from the end of one trip back home or, perhaps, to the beginning of another. Figure that and the current ride-hailing fleet together, and the average trip on Uber or Lyft creates 50% more harmful air emissions than the average car trip.

As environmental groups have argued, with disruption comes responsibility—to grow by encouraging zero-emissions vehicles, and do so in a way that’s sustainable and economically viable for their drivers.

The method CARB is proposing isn’t dictating any models for ownership—amid the state’s pending lawsuit against Uber and Lyft over alleged labor-law violations—and it will have higher standards for the large tech companies than for a small ride-sharing or ride-hailing operation.

Uber electric car

Uber and Lyft dominate the market. According to CARB, the two companies combined covered 4.2 billion miles—versus just 5.9 million miles for all smaller transportation network companies combined. It’s proposing a 5 million mile threshold for exemption, which frees the smaller companies from all but data reporting but leaves the option open for future rivals.

How it might work

Regulation will be focused primarily around the idea of % eVMT (electric vehicle miles traveled), and counting only those miles covered by battery electric and fuel cell vehicles. PHEVs won’t be counted because there is no standardized, centralized way of knowing when and how often PHEV drivers actually plug in—with some studies showing that a significant portion never do.

As per SB 1014, the Clean Cars Program will submit its proposal to the CARB board by the end of the year. Network companies would then submit two-year plans by January 2022, but the first compliance year for the new standard would be 2023.

Daily mileage needs of ride-hailing driver <250 miles

Under two preliminary strategies, CARB would bring the percentage of eVMT from an estimated 5% in 2023 up to either 32% or 51% in 2030—and lower emissions from 250 grams per passenger mile traveled today to between 38.4 and 68.6 grams in 2030. Overall, the strategies could raise the number of zero-emissions vehicles actively used in ride-hailing to 400,000 by 2030.

There’s likely some revisiting to be done in light of the pandemic. The state was planning to promote the use of pooled trips through its compliance calculations, but all pooling has been suspended indefinitely for both Uber and Lyft and current events might change the long-term assumptions. Officials also pointed to the closure of GM's Maven, including Maven Gig and the corresponding service allowing rentals of the Chevy Bolt EV.

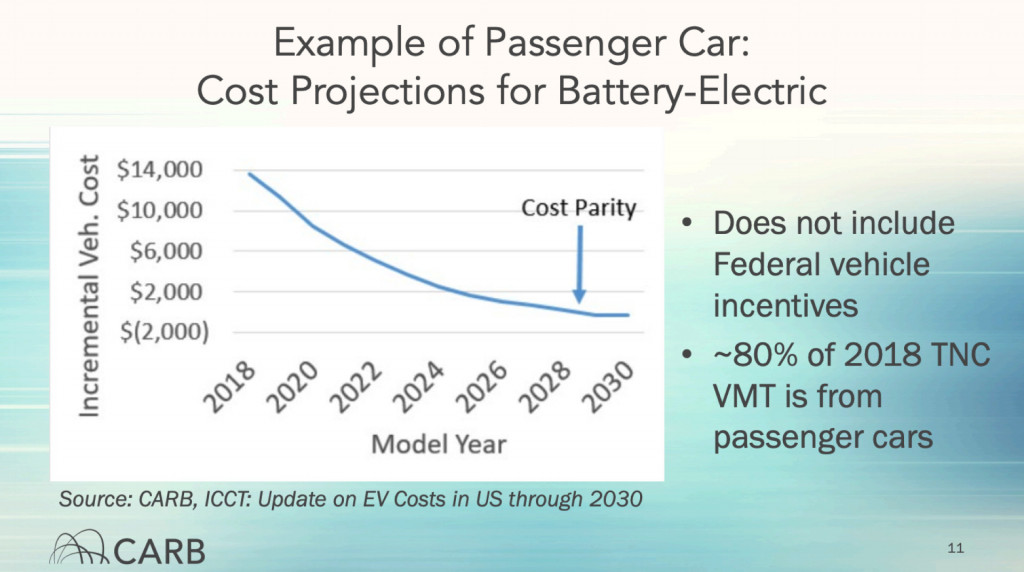

CARB - cost parity with gasoline by 2029

The targets were established largely based on the break-even costs for drivers—assuming a cost parity with gasoline vehicles by 2029 and essentially leaving the business model to adapt to economic realities in the interim (again depending on how the state’s challenge of independent-contractor status).

What you can do

CARB officials said that they have not yet gotten to the point of mapping out enforcement, or whether there will be fines or a mechanism like ZEV credits. It’s currently welcoming alternatives for the proposed methods that can achieve the same benefits at a lower cost, and asking for comments by June 15.

It’s also examining the possibility of including hybrids in the regulation, or an alternative that would require all ride hailing in the state to go all-electric by 2030.

Both Uber and Lyft have environmental initiatives, but neither has put a substantial percentage of EVs in service—even in California. Lyft, for instance, has been offering electric cars via its Express Drive program, and Uber has been paying its electric vehicle drivers a higher rate.

Lyft car picking up a rider

Consumer Reports noted last week that the full return on the cost of switching to an EV under the program should be realized after just a year. “By embracing policies and technologies that have the potential to reduce pollution and congestion, ride-hailing companies will be better equipped to fulfill their promise to consumers,” said CR’s policy analyst Alfred Artis.

“We believe that the ride-hailing industry will eventually thrive in California,” said Joshua Cunningham, chief of the Advanced Clean Cars branch of CARB, who emphasized the importance of the program in lowering emissions longer-term.

The pandemic might give ride-hailing companies a much-needed chance to reboot and refocus. And if you’re given the chance to choose an electric ride—maybe even one that costs a little more—showing them that the demand exists would likely do a lot of good.