Recent Updates

01/19/2026 12:00 PM

New 2027 Ford Bronco: CEO hints at name for crucial Kodiaq rival

01/19/2026 12:00 PM

We try Audi’s new tech innovations – with sideways consequences

01/19/2026 12:00 PM

My pledge for 2026? To road test the GMA T50

01/19/2026 12:00 PM

Used Suzuki Ignis 2016-2025 review

01/19/2026 12:00 PM

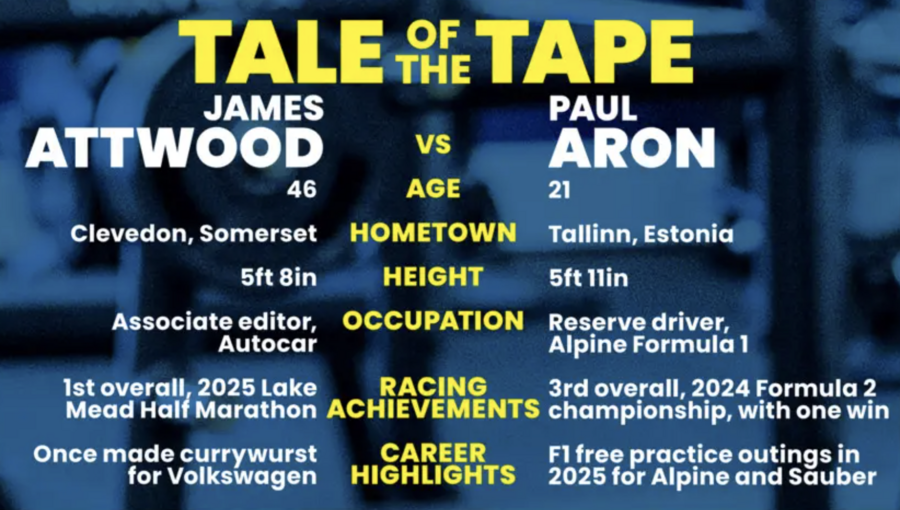

Autocar writer vs Alpine F1 driver: Who is fitter?

01/18/2026 12:00 PM

Getting an old Peugeot 205 (and its driver) through UK's toughest rally

01/18/2026 12:00 PM

Is that a Supra...? Yes, it's mine - and it's got 160,000 miles on it

01/18/2026 12:00 PM

The UK's best cafes are at the side of race tracks. Yes, really

01/17/2026 12:00 PM

Don't make M like they used to... M2 CS vs M3 CSL and M5 CS

01/17/2026 12:00 PM

My Renault Clio 182 Trophy proves old hot hatches do it best

EV, Hybrid, Hydrogen, Solar & more 21st century mobility!

Some people insist that you don’t have to be very fit to drive an F1 car. Some people are wrong

Some people insist that you don’t have to be very fit to drive an F1 car. Some people are wrong

It’s not long after Paul Aron, Alpine’s Formula 1 reserve driver, arrives in the gym at the team’s Enstone factory that I realise I’m in trouble.

"What’s the record?" he asks as the first exercise is explained to us. Turns out Aron is 21, ultra-fit and hugely competitive. Of course he is: he’s a racing driver. Racing drivers are competitive at everything, even when taking on a random car journalist in a fitness challenge. Win? I just want to survive.

With hindsight, this was never going to end well. The basic idea was that both racing drivers and car journalists drive cars for a living - and some people insist that you don’t have to be very fit to drive a car. So we wanted to find out how important fitness really is in F1.

After all, teams now employ ranks of trainers, sports scientists and nutritionists to help drivers cope with the incredible forces of a grand prix car and perform at their peak.

You won’t find many sports scientists on the average new car launch, which could be why ‘launch paunch’ is common industry parlance. Still, having once been a lot bigger than I am now, I like to keep fit and can run a marathon in just over three hours, which is, without trying to sound boastful, quite a bit quicker than average.

"You look like a runner," says Aron, giving me brief hope that he might be intimidated by a 46-year-old hack, before adding: "Luckily, that’s not a big part of race fitness." Rats.

Clement Le Viennesse, a doctoral student in sports science, is on hand to put us through a workout devised by one of Alpine’s driver coaches. We start with neck work, using a flex strength machine. Aron and I take turns to don a head harness that looks a bit like a rugby prop’s scrum cap.

Le Viennesse then hooks it to a short elasticated cable that is, in turn, attached to some weights. We have to sidestep away from the machine and then perform lunges, keeping our neck straight to build strength in the muscles without hurting them.

It still hurts. I struggle with just over 6kg attached on either side. Aron insists on trying 17kg and lunges away with disarming nonchalance.

The Estonian does have a relatively thickset neck and says he didn’t really struggle with the forces a single-seater exerts on those muscles until he reached F2. "Your neck is always adapting to a quicker car," he adds.

That said, he acknowledges that there is a vast jump from F2 to F1. Having been part of the Mercedes F1 junior programme from 2019 until 2023, he joined the Alpine F1 Academy in 2024 and his first chance to drive an F1 car came in the post-season test in Abu Dhabi.

This year he has been an official Alpine reserve driver and has appeared in four Friday practice sessions with Alpine and on loan to Sauber. "In my first test, I had to put extra padding in the cockpit surrounds halfway through the day, because my neck was done," he says.

"The first time you drive an F1 car, it will be difficult, no matter how much you’ve trained. This year, I’ve gone months between driving the car, and every time I get back in, it’s a shock."

After working on the sides of the neck, we switch to the back: with the immense braking forces of an F1 car, resisting your head being thrown forward under braking is hard. I’m better at this, handling 14.7kg while lunging. Then Aron hooks up 26kg with ease and makes me look daft again.

The next exercise develops lower body muscles, key to building the strength needed to hit the brakes and slow an F1 car from 200mph to a halt. We use a weight machine that you lie on.

Le Viennesse instructs me to press one foot against a panel; the lock is then released and I have to hold the panel with my knee bent, before then rapidly pumping it 10 times. It does feel a bit like I’d imagine slamming on the brakes in an F1 car would - flipping hard work, basically. And that’s without any weight hooked up.

Aron says the strength needed to apply brakes changes as you rise through the ranks. F3 cars use steel brakes, "so you just smash the pedal as hard as you can and you’ll never have a problem", but the carbon brakes in F2 are too powerful for the car, "so braking too hard can be a bad thing".

Aron, needless to say, clips on a load of weights and makes it look effortless.

His commitment to fitness is clear. It even predates his car racing career, stemming from lessons he learned playing football at school. "The team I played for won the Estonian age-group championships a few times," he says.

"I was never really that skilled compared to some of my team-mates and I knew it - but I worked much harder. It’s how I kept my place: I was a midfielder and I was always running everywhere."

That grounding in the importance of combining effort and skill has resulted in his focus on fitness. That shows up again in some work on our core muscles. We stand on pads that weigh us and then have to jump as high as we can, keeping our legs straight and limiting arm movement.

I struggle to crack 25cm. Aron eclipses 40cm. Mercifully, my slow pace and Aron’s insistence on multiple attempts to break the record for each piece of equipment mean time is short. We skip the upper-body strength and endurance workouts.

Fitness being a lost cause as a competitive contest, we move on to the cognitive and reaction tests. These are more sedate. There’s an old F1 steering wheel that has been turned into a reaction test: press neutral, pull the clutch paddle in, engage first gear, watch the lights on the wheel turn red and, when they go out, release the clutch.

After several goes, my best reaction time is 217 milliseconds. Aron manages 160. Sadly, though, Aron insists even this doesn’t qualify me to be an F1 driver.

"In this, you just dump the clutch, but in reality you have to manage it," he says. "You can give away a few hundredths in reaction time, but you will win more time if you have better clutch management and throttle application."

The final test is based on Batak; it’s a touchscreen that presents dots which you have to press as quickly as possible. I’m encouraged to manage 37, as Aron achieves 39.

Aron says the reaction exercise helps him less with reaction time than with boosting awareness, such as how to spot other cars in his peripheral vision. He cites Max Verstappen’s situational awareness at the start of races, knowing where he can place his car on track.

Forget racecraft: on today’s experience, I would barely be able to get around a handful of corners in an F1 car before my body cried enough.

And given that I’m pretty fit for a car journalist, it’s a humbling demonstration that, even if they sit down driving all day, racing drivers are supreme athletes.

Perhaps my only hope at beating Aron comes from his confession that he can’t sing. Rematch at karaoke? Hang on: I can’t sing either...

Why motorsport is playing catch-up

Clement Le Viennesse began his career in sports science working in track and field, before a master's in neuroscience led him to take on a PhD about neuromuscular fatigue that had relevance to motorsport, which led him to his current role at the Alpine F1 team.

He says awareness of fitness is growing rapidly in motorsport but there's still huge potential to unlock. "In track and field, we know everything about athletes," he says. "We have video analysis, forces decks and more, so we know their strengths and weaknesses. When I moved into motorsport, it was like: 'Oh, wow, there's no data."

That's why Alpine is starting to build up ways of testing and evaluating driver fitness, although, given the varied demands compared with singular track and field athletes, it's a work in progress.

But it's also about education, says Le Viennesse: "In the Academy, we have some young drivers in karting who have never been in a gym before and don't see how physical and cognitive fitness is important. Our role is to make them understand."