Recent Updates

02/18/2024 12:00 PM

Fiat 500 Hybrid

02/18/2024 12:00 PM

How the Czinger 21C will change car manufacturing for good

02/17/2024 12:00 PM

Inside Meyers Manx: the most fun car company in the world?

02/17/2024 12:00 PM

Will phone payments make car park machines obsolete?

02/17/2024 12:00 AM

Volvo XC40

02/17/2024 12:00 AM

Best cars for £15,000 and under

02/16/2024 12:00 AM

JLR slows electric car blitz but boosts PHEV output

02/16/2024 12:00 AM

Peugeot 3008

02/15/2024 12:00 PM

Ex-JLR design boss Massimo Frascella replaces Marc Lichte at Audi

02/15/2024 12:00 AM

Official: Lancia Ypsilon reborn as EV supermini with 250-mile range

EV, Hybrid, Hydrogen, Solar & more 21st century mobility!

![Czinger 21 C front three quarter lead] Czinger 21 C front three quarter lead]](https://www.autocar.co.uk/sites/autocar.co.uk/files/styles/car_review_image_190/public/images/car-reviews/first-drives/legacy/czinger_21_c_front_three_quarter_lead.jpg?itok=tzQVwlrU)

Czinger plans to sell 80 21C hypercars at £2.2 million eachThe same American firm that is looking to "obliterate track records" also makes an AI-designed, 3D-printed supercar

'Doing the bare minimum’ as a phrase has pejorative connotations.Â

It implies an element of coasting, refusing to surpass expectations and settling for mediocrity – even, perhaps, giving up. But here we are in 2024, when manufacturers (not just of cars) are confronted with soaring production costs and are rigidly committed to reducing their impact on the environment.

Products mustn’t just be cheaper to make: they must also be lighter than ever before, use minimal materials in their make-up and be fabricated rapidly, using as few resources as possible. Doing the bare minimum, it is clear, is now nothing less than an overarching objective for the industry.

Nowhere is that felt keener than at 19601 Hamilton Avenue, Torrance, California, otherwise known as the headquarters of manufacturing masterminds Divergent – or, as it will no doubt soon come to be known, the epicentre of a bold new era for the automotive industry.

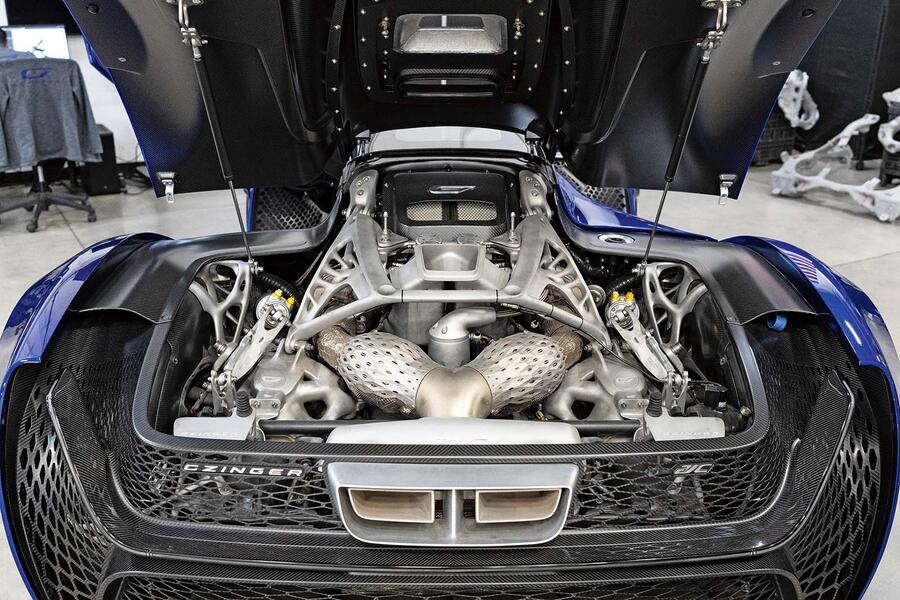

Divergent is best known for being the parent firm of Czinger, creator of the ludicrously powerful and fascinatingly engineered 21C hypercar – a 1233bhp V8-powered showcase of what can be achieved with the firm’s new-school approach to vehicle manufacturing.

![]()

When it was revealed back in 2020, the 21C quickly came to be known as the ‘3D-printed hypercar’, which is a description that is at once both vaguely accurate and something of an undersell. Because there’s surely no car, road-going or otherwise, being built right now, anywhere in the world, that can lay claim to such beauty in its engineering.

Its rear subframe twists and wraps hypnotically around its masterfully presented engine, free of unsightly welds and clearly as light as it could possibly be without sacrificing a mite of structural integrity.

Its intimidating, ground-sucking aerodynamic addenda – generating 2000kg of downforce at 190mph – speaks of its track-honed performance potential. And its cockpit would seem to have been lifted straight from a Le Mans Hypercar were it not for a centrally positioned driver’s seat and another behind for a lucky passenger.

President and chief operating officer Lukas Czinger tells me that Czinger is “a business in its own right†and lays bare his ambition for it to become “the most successful American performance car companyâ€. But more importantly, the 21C serves as a “laboratory on wheels†to both showcase and further the development of manufacturing innovations by the parent firm.

“Divergent’s mission was a very, very ambitious and broad one: a system-level solution to design and manufacturing for automotive body-in-white and aerospace and defence structures,†he explains. “We looked at their traditional way of making and designing things, which had some pretty good digital tools but not a lot of automation driving that design process.â€

It wasn’t just the design process that Divergent wanted to overhaul – Lukas believes the whole vehicle manufacturing process is “broken in multiple waysâ€. That’s primarily because the conventional process of producing a body-in-white “takes a ton of energy and time†and emits a substantial amount of CO2 but also because the established methods of development and construction are needless drains on company resources.

“The capital cycle of automotive is unforgiving,†he says. “Even the best in the industry are struggling over 10- or 20-year periods, because it’s such a capex-intense industry, and most of the capex is coming from producing the body-in-white of that vehicle. So you need to spend a large lump sum up front – lock all of that money quite literally in stamping dies, casting equipment, welding equipment, setting up your body-in-white facility – and then hope you sell x number of units per year.â€

Essentially, the profitability of any given vehicle is bound up in how quickly its maker is able to amortise the costs of tooling up a factory to build it, and that’s why we are all now so familiar with the standard seven- to eight-year model life cycle, usually with a light styling update at the halfway point.

Designers and engineers might want to make improvements to the car sooner than that, but they are prohibited from doing so by the need to generate a healthy return on the investment that was made at the starting point.

The solution to all of the above – and the reason why we are here – is Divergent’s asset-light and ultra-efficient ‘three-pillar’ approach to design and production.

The first pillar is a new artificial intelligence-powered design programme, coded by the company’s own crack team of engineers, that quickly arrives at the optimum design for any given component – the one that is the lightest, most rigid and most durable while using the absolute minimum amount of material.

Lukas believes this system has the potential to turn the automotive engineering industry on its head.

He explains: “From a control arm to the rear frame of a vehicle, when we as design engineers are doing designs, we’re just stopping once we get below the requirements and saying: ‘This is a pretty good design. Maybe we’ll do another loop or two, but we’re not going to do 10,000 loops to find the true global maximum point.’

"But our piece of software will do 10,000 loops, run that full workflow and converge on a global maximum where you actually can’t take a gram of material out of the design. You can’t change that part without giving up one of your performance requirements. This is the rawest form that component can be.â€

Producing components to this ultra-stripped-back formula is impossible using conventional stamping, casting or machining practices, hence Divergent’s use of ‘additive manufacturing’.

Which brings us to the second pillar, the pièce de résistance of the company’s operations: an imposing ring of 22 towering robotic arms, programmed to work together to ‘print’ an ultra-light, ultra-strong and utterly resource-optimised metal structure – be it a car’s lower suspension mount, a motorcycle’s swing arm or even a military aircraft’s fuselage – in its centre.

The arms are asleep when we visit and we’re politely asked not to take pictures, but it’s plain that what we’re looking at represents no less than an all-out rethink of the accepted methods of manufacturing.

It is essentially a 3D printer, says Lukas, but rather than weaving simplistic and relatively fragile structures out of plastic or composite, it uses a recyclable aluminium-based alloy, the chemical structure of which (one of 650 patents registered by Divergent) has been devised by the company’s own machine learning-based system (a kind of AI).

It is weldable, so the structures produced can be fixed together by conventional means, but Divergent mostly uses its own ultra-strong adhesive (another patent), which cures in just two seconds beneath an ultraviolet lamp.

“That’s how you can do millions of [cars] a year,†says Lukas. “If it’s 10 seconds or 40 seconds, all of a sudden none of it works.â€

Once the parts are all produced, it’s onto the third pillar: assembly.

Lukas explains: “If you have 40 printed parts, how can you put them together in a way that’s digital and extends all the benefits of general design and additive manufacturing into final assembly? We needed to architect an assembly system which was product-agnostic, so the same group of robots could assemble a Ford frame or a Ferrari frame – hypothetically – on the same exact hardware.â€

With that system now in place, Divergent has signed up its first customers and begun to scale up the business globally. The idea is that this will become the “world’s largest manufacturing platformâ€.Â

Customers will use the company’s software and additive manufacturing system at their own sites to accelerate, reduce the cost of and mitigate the environmental impact of their activities, with the result that they then have freedom to become “design-led companiesâ€.

Component design goes from around 18 months to a matter of weeks, according to Lukas, and there’s no conventional prototyping process to factor in, so “as soon as that design is done, your part is typically right first timeâ€.

Furthermore, the lack of hard tooling means designers and engineers have more freedom to change the product once it is already on the market, with no need to consider the millions of pounds invested in the production of a specific grille panel or suspension mount, for example. Essentially, additive manufacturing “massively de-risks the design you’ve made from a capital standpointâ€.

In this sense, Divergent has the potential to be the world’s most flexible and cost-effective manufacturing partner, claims Lukas: “We’re like [contract manufacturers] Foxconn or Magna on steroids, except we’re 100% flexible to our product mix.â€

There are also huge sustainability implications, explains Kevin Czinger, founder of Divergent and – you guessed it – Lukas’s dad.

“Imagine taking 20%, 30% or 40% of the mass out of structures while keeping or improving baseline crash [safety] and performance: that’s where you reduce the impact on the planet,†he says. “It’s called dematerialisation: a beer can 50-60 years ago required 83g of aluminium. The wall of the can got thinner and thinner and they developed a different tab, so that’s now 12.7g.â€

Appropriately, Kevin sums up the entire process with the ‘four Ds’ (4D, get it?): digitise, dematerialise, distribute and democratise.

They didn’t get here overnight. Divergent generated no revenue in its first few years of operation and is still making fewer than 10,000 parts per year as it finalises its processes and seeks customers.

But the future is bright: the Czingers forecast that it will go from generating tens of millions in revenue now to hundreds of millions as early as 2026, when it plans to be making hundreds of thousands of parts.

All operations are currently based at the firm’s 100,000sq ft headquarters near Los Angeles, but they are aiming for 30 facilities globally by 2030.

Divergent is currently working with seven global car makers, but the only two to be named publicly are Aston Martin, which used a 3D-printed rear subframe for its limited-edition DBR22 speedster, and Mercedes-Benz. And as it seeks to build a larger global network of interconnected manufacturing systems, its sports car firm will take on a new importance as a brand-building technological showcase.

The 21C has already smashed the production car lap records at the Circuit of the Americas – by some 6sec – and at Laguna Seca, where it pipped the McLaren Senna by 2sec.

Does the Nurbürgring beckon? “We’ve made the statement that this is the world’s fastest production car on track and we intend to make that statement good,†grins Lukas, suggesting, perhaps, that the Mercedes-AMG One might not be safe at the top of the tree in Germany for much longer.

But while Czinger is keen to “obliterate track recordsâ€, Lukas says the 21C stands mostly as a headline-baiting demonstration of the wider implications of Divergent’s technology: “Five to 10 years from now, you will look back and see that 21C was the first instance of a vehicle designed and built on this system. That will be powerful. And I think a lot of other cars will be built that way."